The Eighty Years' War - Consolidation of the Dutch Republic

Prince William I of Orange

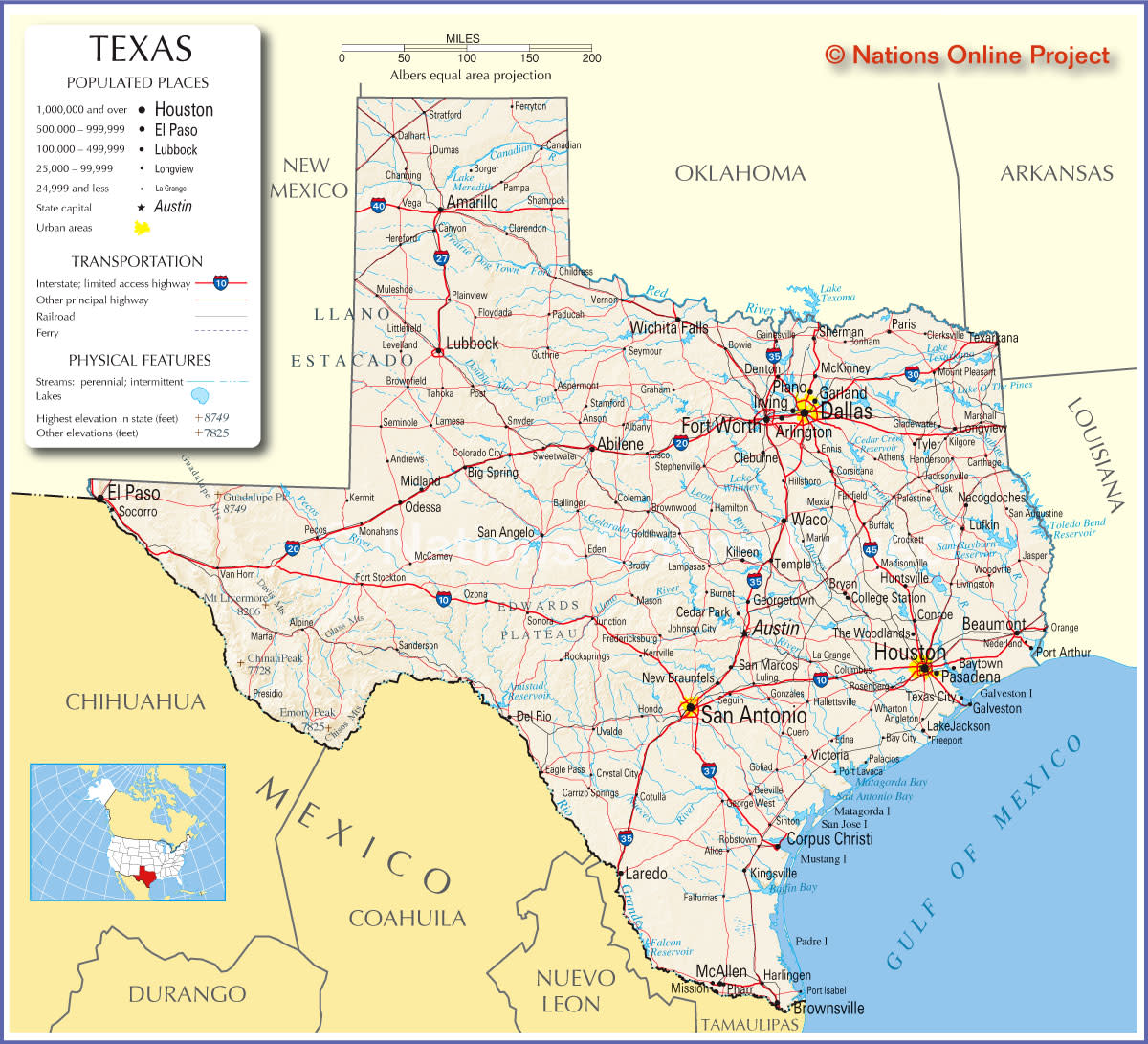

The Dutch Republic was formed as a result of the Union of Utrecht (1579) and Act of Abjuration (1581). With these, the Dutch declared their independence from the Spanish-Habsburg King Philip II. (For more about this, see here.) Needless to say, Philip did not appreciate being set aside like that, and he wasn't going to just let it go. The result was a military conflict known as the Eighty Years' War.

This hub explains how during the course of the Eighty Years' War the Dutch Republic decisively won its independence from the Spanish monarchy, and became one of the wealthiest and most powerful countries on earth in the process.

A note on stadholders

The term stadholder is extremely important in the context of the Dutch Republic. Under the monarchy, the king had employed stadholders to act as his royal representatives in his absence. Because Philip's realm was so large and fragmented, he could not personally be present in much of his territory. The stadholder was a high government official of noble birth who would act on the king's behalf. The term stadholder is derived from the Dutch stadhouder, which literally means 'placeholder'.

After the Act of Abjuration the stadholder technically no longer served a purpose. As William of Orange was a leader of the revolt, and because the provinces needed a single political and military leader, the office was left in place.

William of Orange

The fledgeling state was facing the military might of the Spanish empire, at that time one of the most powerful countries on earth. The odds didn't look good for the Dutch. Their only hope was a strong leader, who could act as a rallying point and command the army. Prince William I of Orange was the man for the job.

William had been raised at the court of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, King Philip's father. He was an experienced diplomat, politician and soldier. Prior to the Act of Abjuration, after which the seven Dutch provinces no longer recognised Philip's rule, William had been the king's Stadholder.

As the prince of the independent principality Orange (a city in modern day France), William was a sovereign lord in his own right. This meant that he was technically of equal rank to King Philip, or any other monarch. In a society where rank and birth were everything, this was a crucial in his ability to command respect in diplomacy and the army.

William thus led the armies of the new republic for the first few years of the war. Unfortunately, in 1584 he was killed by an assassin. There was no obvious candidate to replace him. William's son Maurice was only sixteen and too young.

Prince Maurice and Johan van Oldebarneveldt

For a time, the war went very badly for the Dutch Republic. The country was leaderless, and the Duke of Parma, the new commander of the Spanish army, proved to be a capable general. Spain was rapidly taking back control of much of the southern Netherlands.

The Spanish, however, became overconfident. They bit of more than they could chew when they sent their armada to invade England at the same time as they were fighting the Dutch. The historic English victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588 was a turning point. The loss of their armada was a devastating blow from which the Spanish did not easily recover.

In the meanwhile, the Dutch Republic was also recovering from the power vacuum that had occurred after the death of William of Orange. Prince Maurice had come of age, and quickly displayed a remarkable talent for military leadership. Politically, the Republic had found a strong leader in Grand Pensionary Johan van Oldebarneveldt. In the capable hands of those two, the Dutch Republic now found itself very successful in the war for the next ten years.

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, however, the Dutch advance had lost momentum. They could no not push back the Spanish any further, although the Republic was not losing any ground of its own. The two forces were more or less evenly matched, with neither side managing to gain the upper hand over the other.

The Twelve Years' Truce

Under these circumstances, both parties were willing to negotiate. It did not come to a settlement of peace, but in 1609, the Dutch and Spanish did agree to the Twelve Year Truce.

The Dutch used the truce to develop their country. Political issues about governance that had remained unresolved were tackled. With the outside threat of war gone, it was a time of much internal trouble.Though the country's independence was still formally disputed by Spain, the Republic established its diplomatic presence around Europe, and in practice became recognised as a state in its own right. The peace also allowed the Dutch to expand their mercantile network, which grew rapidly during these years.

Prior to the formal end of the truce in 1621 there were negotiations in an attempt to end the war once and for all. At this point, even the Spanish no longer questioned that the Republic would retain its independence, but there were disagreements on religious and economic policy. The Spanish demanded that Catholics living in the Republic would be given full freedom of religion. They also wished that the Dutch would give up their trade with the East Indies. Neither conditions were acceptable to the Dutch, and so hostilities resumed.

Eighty Years?

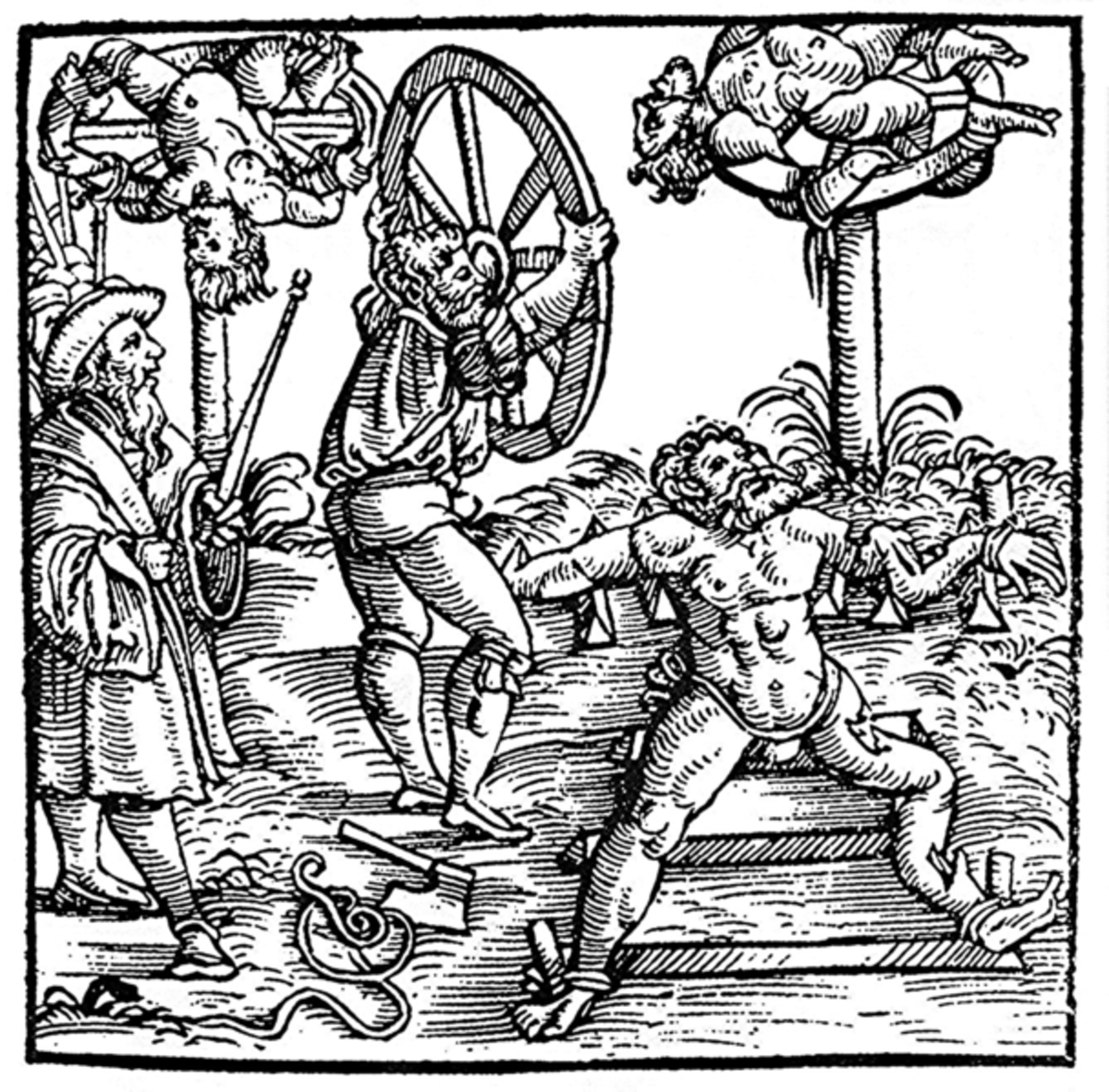

If you look back to the date of the Union of Utrecht, the earliest act towards independence, you will notice that 1571 to 1648 (the signing of the Peace of Munster) is 77 years, not 80. The Peace of Munster was actually signed on the eightieth anniversary of the execution of Counts Egmond and Horne, two leaders in the earliest protest against the Spanish monarchy. Most modern historians now consider the Union of Utrecht as the actual start of the war, but the term Eighty Years' War has stuck and is probably easier to use than the alternative.

The Peace of Munster

After the truce ended, the Spanish initially had the upper hand. They captured a number of cities in the southern part of the Republic.

Prince Maurice died in 1623. Under pressure from the Spanish forces, there was a need to replace him with another strong military leader. The obvious choice was Prince Frederic Henry of Orange, another of William I's sons. Like his half brother Maurice, Frederic Henry had a talent for military tactics, and he would prove to be highly successful in his command of the Dutch army.

A key point in the war came when privateer Piet Hein captured the Spanish treasure fleet in 1628. The fleet had been transporting South American silver to Spain. It is estimated that the treasure may have been worth billions, and it would allow the Dutch to fund their armies for years to come, while crippling the Spanish economy at the same time.

The Dutch also entered into an alliance with France, which saw the Spanish Netherlands attacked from two sides. The Dutch were thus firmly in control of the situation, although they never managed to beat Spain outright.

While Frederic Henry was alive, he strongly opposed any peace treaty, but after his death in 1647, it was not long before negotiations were opened. At this point, both sides were fed up with a war that had not actually been going anywhere for quite some time. The Peace of Munster was concluded a year later, in 1648.

Celebrating the Peace of Munster

A Golden Age

The Dutch Republic emerged from the Eighty Years' War not only with its independence finally recognised by Spain, it had by then become one of the world's wealthiest and most powerful countries.

The seventeenth century, and particular the first half, is generally considered to be the Golden Age of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch greatly expanded its trade network, both in Europe and all over the world. The VOC, the Dutch East India company, was founded in 1602 and rapidly established numerous trading posts in Asia. Amsterdam became Europe's warehouse; if it existed, it could be bought there. With the wealth flowing in, the arts flourished, as is evidenced by the paintings of the Dutch masters that are now treasured in museums all over the world.

Using its wealth, the Republic was able to built a powerful army and navy. For a time, the Dutch would rule the seas and play a dominant role in the world.